Spaces and Storytelling in The Shining

Above: The vast Overlook Hotel.

I.

An enormous, abandoned, unreachable hotel; a delusional, axe-murdering psychopath; a clairvoyant, telepathic child; and a frail, scared young woman: a cursory list of elements in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining would seem to position it squarely within the horror film genre. Couple this with the fact that it shares these elements with an earlier novel by Stephen King, who has built an entire literary career out of manipulating the narrative conventions of the American ghost story – a genre that has been part of our oral history since the start of European settlement in the 1600s – and you might have the beginning of argument that places King’s text at the center of the film’s success. Kubrick’s adaptation does share several key elements with King’s original, including a certain foundation in genre, but few critics attribute the film’s success to King. Even King’s fans do not claim it as one of “the master’s.” In a pamphlet entitled “The Films of Steven King,” enthusiast Michael R. Collings admits,

the best approach to Kubrick’s The Shining is to divorce it from any connections with Stephen King – not because Kubrick failed to do justice to King’s narrative, but simply because it has ceased to be King’s.

Cultural critic Frederic Jameson takes this argument even further, writing in his book Signatures of the Visible that “the genre does not yet transmit a coherent ideological message, as Stephen King’s mediocre original testifies.” Indeed, as Jameson suggests, Kubrick’s adaptation, while it maintains elements necessary to cue the genre of the horror film, expands King’s work of popular entertainment into a thoroughly postmodern work of art.

Definitions of “the postmodern” and of “postmodernity” can often be as numerous as the theorists articulating them. Here, “postmodern” will follow Jameson’s construction of the term, which identifies postmodern culture through several specific characteristics. One of these characteristics is a pervasive sense of “depthlessness” that infiltrates the postmodern work. With this notion, it is easy to show how Kubrick’s changes have a “postmodernizing effect” on King’s original text. Where King’s Wendy and Jack Torrance are strong and intelligent, Kubrick’s Wendy and Jack are flat and ordinary. At times, Kubrick treats them in such a “depthless” way that it is impossible to believe they’re thinking characters at all. Their dialogue, often sounding rehearsed and stiltedly delivered, suggests a “flattened” human psyche, and these “depthless” characters bring with them a flattening on the film’s thematic and metaphysical levels: where King’s story is an epic of Good versus Evil, Kubrick’s film is more ambiguous. The vast rooms and labyrinthine corridors of the Overlook are the spatial and thematic axis of Kubrick’s film (there are few scenes that take place outside of its walls), and Kubrick finds his greatest metaphor in an image of his own invention, the hedge maze.1

In examining the transition from book to film, the totality of Kubrick’s new vision for King’s generic story is clear, and the correspondence between Kubrick’s new vision and Jameson’s specific ideas about postmodernity are felt. Jameson discusses the film at length in an essay called “Historicism in The Shining.” In it, Jameson reads The Shining in terms of another of his characteristics of postmodernity called “historicism,” defined as “the random cannibalization of all the styles of the past” by postmodern culture. He suggests that

the nostalgia of The Shining, the longing for collectivity, takes the peculiar form of an obsession with the last period in which class consciousness was out in the open (the 1920s): […] this is, finally, what The Shining is all about.

Jameson argues that through its use of the horror film genre, The Shining creates a “pastiche,” a particular breed of historicism in which the stylistic attributes of a genre are cannibalized by a work while the work makes reference to this process.2 This obsession with the past pushes the film into nostalgia, and the function of this nostalgia today is to describe a present that is so full of pasts that any present subject’s sense of present self is overwhelmed by the past’s enormity. If pastiche is a symptom then nostalgia is the affliction, the condition of souls in love with the past while it destroys them in the present.

Jameson insists that “beauty and boredom” are at the heart of the The Shining’s present, and, using the opening sequence as an example, he suggests that its establishing shots of “picture-postcard” landscapes and idyllic hotel life are nasueatingly “beautiful” and tritely “boring.” He thinks the “great swathes of Brahms” create a sense of “cultural asphyxiation.” But to describe the opening shots of The Shining in this way is to neglect many of their compelling formalities. There is the disturbing, quick movement of the camera, its brief pursuit of a car and then its dissolution into aimless panning about, and the eerie descant of screeches and aquatic garbles added over the classical music: all of these features, which Jameson neglects to note, bring this opening sequence out of the realm of “beauty and boredom.” Again and again Kubrick plays these particularly “filmic” attributes of movement and sound against the on-screen images of The Shining, and again and again Jameson fails to notice them. His neglect of the filmic attributes of The Shining later causes him to dismiss Danny’s telepathy as a generic “false lead,” but it is hardly that: Danny’s “shining” is one of Kubrick’s principal interests in the film itself, as we will see. Rather than faulting Jameson for this mistreatment and abandoning his thinking as a tool for understanding the film, I would like to suggest instead that Jameson’s best formulation for reading the filmed events at the Overlook Hotel is, in fact, an essay that deals with the real events at another hotel altogether.

Above: The soaring Westin Bonaventure lobby.

II.

That hotel is the Westin Bonaventure of Los Angeles, created by architect and developer John Portman, and Jameson’s observations about it reverberate throughout his essay entitled “The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism” (1991). In the opening paragraphs of the essay, Jameson writes,

[I]t is in the realm of architecture, however, that modifications in aesthetic production are most dramatically visible, and that their theoretical problems have been have been most centrally raised and articulated; it was indeed from architectural debates that my own conception of postmodernism – as it will be outlined in the following pages – initially began to emerge.

Using recent trends in architecture as a basis, Jameson extrapolates five general trends, two of which – depthlessness and historicity – we’ve already explored.3 These trends, however, come at the start of Jameson’s argument and were formulated nearly a decade before his Postmodernism project (in which “The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism” appears) was published, as his 1981 essay on The Shining demonstrates. While the earlier two trends shed a certain degree of light on the complexities of the film, the three new trends Jameson articulates in “Cultural Logic” – a new sense of space and spatial logic in the temporal arts, a variation on an older notion of “the sublime” native to postmodernity, and a re-envisioning of architecture as a unique and powerful language – have an analytical impact that is far greater than that of the earlier two.

Above: Grady and Jack in the restroom. Below: Grady’s twins in the hallway.

First among Jameson’s new trends is a new sense of space and spatial logic in the temporal arts. Jameson’s formulation of this trend can be split into two parts, the first of which, perhaps ironically, is schizophrenia, which arises for Jameson when the temporal structure of language – one word following another in time – breaks down, and how meaning is made thorough language becomes more like how meaning is made through imagery, where all signs exist together in a non-linear present, with past and future erased. With this idea we can describe Jack Torrance’s madness in The Shining as schizophrenic according to Jameson’s terms. Jack finds himself, upon arriving at the Overlook Hotel, to be stuck in a perpetual present. “I’m having the most extraordinary sense of déjà vu,” he tells Wendy shortly after Closing Day, “I feel like I’ve been here forever.” Indeed, he has been there forever, as Grady informs him in the restroom – “You, sir, are the caretaker. You have always been the caretaker” – and he will be there forever, preserved, at the end of the film, in ice on the lawn and in a photograph on the wall. Wendy, as her name suggests, is portrayed as a kind of female Lost Boy or Raggedy Ann, pre-fertile, in spite of Danny’s strange birth, and caught in the same Neverneverland as her husband, whose force of age has been rendered just as impotent.4 The only grown-up, it seems, is Danny boy, whose unique gift enables him to communicate without being locked up in what Jameson has described elsewhere as “the prison-house of language.” Indeed, Jameson’s description of a schizophrenic “ideal” bears a remarkable resemblance to Danny’s extraordinary visions:

The signified […] is now rather to be seen as a meaning-effect, as that objective mirage of signification generated and projected by the relationship of signifiers among themselves.

The second part of Jameson’s “space and spatial logic” trend builds on this notion of a schizophrenic ideal. With the breakdown of time, the spatial aspects of meaning are inevitably heightened. This “materiality of perception,” in which the visual no longer needs to be couched in terms of the verbal, induces a dreamlike state in the postmodern subject, who, leaving behind the anxiety and loss of the modern subject’s inability to portray his visual world with total verbal accuracy, experiences a “a euphoria, a high, an intoxicatory or hallucinogenic intensity.” The second part of Jameson’s formulation, then, are these very “intensities.”

The relationship of these “intensities” to The Shining is not difficult to envision; already we have seen how Danny’s “shining” is a rather elevated kind of dreaming or mental projection, locating it precisely within the realm of perception that Jameson describes. But there are other examples as well. Jameson describes the effect of these “intensities” on the subject as being similar to that of a hallucinogenic drug. The only explicit drug use from the film is Jack’s love of Jack Daniels, but, in this context, it seems a watered-down panacea for Jack’s profoundly modern alienation; it is hardly the euphoric, visionary, postmodern drug that Jameson articulates. A more potent – although less explicit – drug in the film comes in the form of television. The kind of hallucinogenic drugs Jameson mentions – LSD, PCP, heroin – induce a powerful euphoria in the user but also prevent an outward expression of this euphoria, such that users of these drugs often appear to be glazed-over, spaced-out, or even “flat.” A similar kind of “flattened” expression comes from watching television. These expressions crop up in The Shining, particularly during those times when Danny and Wendy the spectators, are watching television against a vast scenic backdrop. Jameson suggests that such a scene is typical of “the postmodern viewer” who is “called upon to do the impossible, namely, to see all the screens at once.” And, although we never witness him watching television, glazed expressions also crop up on Jack: during “A Month Later,” he stares glassy-eyed over the hedge maze model, and, during “Thursday,” he looks vacantly into the vast space of the Colorado Lounge. While initial readings of both of these instances may suggest that Jack is slowly losing his mind – of this there can be no doubt – we also see in these scenes Jack’s seduction by the hotel, its euphoric vastness slowly overwhelming him. Subsumed by the sheer size of the Overlook, he loses his hold on the actual world, a world already unappealing to him because of his failings in marriage and fatherhood. Finally, Jack becomes a part of the great hotel.5 By the time that Kubrick shows him on “Thursday,” we are aware that when Jack stares blankly into space, he’s really seeing all the “screens” of the Overlook at once. Jack, too, is converted into a postmodern viewer.

Above: The guest in Room 237.

III.

This absorption and its accompanying sense of euphoric release are both manifestations of a new kind of aesthetic mode, which Jameson dubs a “postmodern sublime.” This new mode brings with it a reimagining of the limits of the man and machine, which is also seen in Kubrick’s film. If Jack’s sense of self is totally overtaken by the Overlook, whose name hints at the visual overload that will be his undoing, then the Jack that is left for viewers to observe on-screen is the mere shell of human being. Though Jack’s empty self is certainly the most important to observe, there are other “false bodies” in The Shining as well, the most infamous of which is the old/young woman in the bath, whose bodies represent the extremes of feminine beauty and grotesqueness, exactly the kind of limits which characterize Jameson’s notion of the “postmodern sublime.” There are also Grady’s murdered daughters who speak and walk in tandem, as if they are puppets animated by their father; or Grady himself, whose bodily appearance in the film Jameson describes in his essay on The Shining:

the film public palpably gasps when the conventions of the ghost story are violated, when the hero physically intersects with his fantasmagoric surroundings and he collides with the material body of a waiter whose drink he spills.

Kubrick plays with the limits of the phantom’s body as he forces ever more content out of Jack’s near-emptied human shell.

Having gutted man’s body, we turn our collective hopes to machinery. The machines of postmodernism are quite different from their clunky precursors; while modern machines are machines of production, postmodern machines are machines of reproduction. Jameson includes a short list of several of these new technologies, which include

movie cameras, video, tape recorders, […and] the computer, whose outer shell has no emblematic or visual power, […] as with that home appliance called television which articulates nothing but rather implodes, carrying its flattened image surface within itself.

If the effect of the television on its viewers is to “flatten” their non-visual senses, making them able to absorb exclusively visual data in real time and without projection or the need for processing and verbal translation, then perhaps television itself may be described this way. Its images, like those hallucinogenic ones in the characters’ heads, are also self-contained without need of projection, processing, or verbal translation of any kind. The “signals” the television receives are beamed through the air impalpably, “shining” on the screen with the same kind of finished completeness as the signals that Danny receives in this own mind. “Shining,” then, is the ultimate metafilmic gesture, for it does not concern itself with any of the material aspects of film, the reels and celluloid themselves; rather, it is the “shining” of light through the retina and into the brain where its communicative apparatus it is entirely unwitnessed and correspondingly unfiltered. It is an activity like that which takes place in the darkened room of the movie theatre, where the audience’s giant, collective eye inhabits an interior dreamspace that is capable of eliciting real responses at the mere “shining” of light on a screen. Jameson anticipates this trend, writing about a high point in postmodern texts, where

beyond all the thematics or content the work seems somehow to tap the networks of the reproductive process and thereby to allow us some glimpse into a postmodern or technological sublime.

The modern movie theater is ideally suited to rendering visual the postmodern sublime. Darkened and sealed, the audience hushed, people are isolated from each other and from themselves by way of the fiction film, a thoroughly faked, seemingly real, totally engrossing bit of fictional evidence, Baudrillard’s “copy for which there is no original.” Cut from reality like a balloon from its cord, the film space rises ever higher into the atmosphere, reaching the seam of representation and divorcing its subjects from it. Jameson’s articulation of his final trend – that architecture is a language unto itself – offers the theoretical tools to discuss this new “hyperspace,” the landscape of the postmodern sublime.

It is to hyperspace that the Torrances travel, the great hotel at the end of the world, its limitless rooms holding limitless schizoid realities. On the way there, Kubrick drops clues about the nature of the location like breadcrumbs,6 for, at the end of the movie, Kubrick leaves us at the Overlook to find our own way out. Clues arise during the Torrances’ car trip. Wendy observes that “The air is awful thin up here,” to which Jack replies, “You’ll get used to it.” Later, Wendy asks, “Is this where the Donner Party got snowbound?” Donny asks what the Donner Party is, and upon Jack’s reply, confesses that “I know all about cannibalism, Mom – I saw it on TV.” Jack’s interview with Mr. Ullman 7 has provided an earlier clue. The road to Sidewinder, he informs Jack, is not plowed during the winter due to heavy snow. With the allusion to the “snowbound” Donner Party, the circumstances of the Torrances’ situation snap immediately into place: they are the Donner Party, snowbound, trapped high above everything in a place that would, at first, seem normal were its air not so strange; they, too, will face cannibalism in the form of a space that has consumed their father already; and we, munching popcorn in a similarly hyperreal space, will watch it, like Danny, shining at us on a screen.

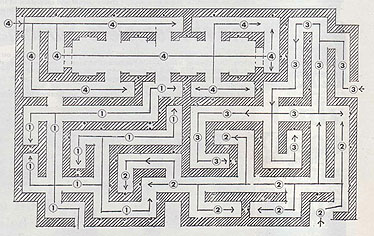

Top: Garrett Brown dons his invention, the Steadicam, during filming in the hedge maze. Bottom: Kubrick’s shooting plan for the hedge maze.

IV.

The Overlook, as hyperreal as a movie theater, is more than the setting for this contemporary horror story; it is a member of its cast of characters, and Kubrick introduces it as such. Mr. Ullman’s winding tour, like the out-of-sequence veering landscape shots of the opening, is given for either the Torrances or the audience to get their bearings.8 Instead, it is to subjectify the setting, to presence the place. His tour guide’s tale of the Overlook’s history is more like a patient’s psychological case history, and the places he walks the Torrances through – the ballroom, the kitchen, the hedge maze (Snocat parked outside) – are all throbbing with potential energy, ready to be set in motion. We are being introduced to these material things for a reason; they will come up again. Le Corbusier’s notion that “the plan is the generator” is all too true here, for the narrative of The Shining is not based on a temporal sequence of events. It is built from the architecture of the Overlook itself. Jameson discusses the idea of this spatial narrative structuring as he talks of Portman’s Westin Bonaventure Hotel, writing that architects like Portman “attempt to see our physical trajectories through such buildings as virtual narratives or stories, as dynamic paths and narrative paradigms which we as visitors are asked to fulfill and to complete with our own bodies and movements.” These “narrative trajectories” make the space the organizer, the teller of the story, and it is for this reason that Kubrick chooses to let The Shining be told from the Overlook’s perspective, all-seeing, tracking each of the characters as they move through its many spaces. From Jack’s first interaction in the hotel – he asks the desk clerk where Mr. Ullman’s office is – the hotel’s ubiquitous eye follows and lurks, anticipating every twist and turn the characters will take in its bewildering corridors, the ultimate postmodern viewer, tracking all three Torrances at once.9

Of course, this more evolved space brings with it more evolved means of navigation. Jameson explains, “[the] new machine […] does not, like the older modernist machinery of the locomotive or the airplane,10 represent motion, [it] can only be represented in motion.” One of the examples of this kind of machine he provides is the helicopter, to which Kubrick mounts a camera for the opening shots of the film,11 but another could just as easily be Garrett Brown’s Steadicam, which was created for and first used during shooting on The Shining. The Steadicam itself is hardly much – a harness that attaches to the cameraman’s body on a pole that allows the camera can pan or tilt smoothly. Like the helicopter, it is defined not by action but by motion. That it comes with a cyborg-like consumption of the human body – the harness is a shock-distribution system – should hardly be surprising, given the postmodern attitude toward the body I’ve described already. The Steadicam represents human motion without representing the human being that is moving; the subject’s self thus stripped, audiences are left to believe that the humans represented on-screen are themselves not fully human.

Above: Danny shines during an outdoor showing of the film at London’s Somerset House.

V.

If King’s book has characters relating to one another, Kubrick’s reformulation gives us characters whose selves have been transplanted or left out altogether. Any trace of Wendy’s motherhood has long since vanished. Danny’s “deep sight” is, in fact, aided (he believes) Tony, who lives in his stomach, though it may be that Tony is the “shining” itself. Jack’s soul has been given to and distributed throughout the great hotel that collects souls like trophies on a wall. These infestations, these parasites, while they serve as metaphors for the false sense of self-awareness experienced by the postmodern subject, actually serve as metaphors for a great deal more; namely, the relationship of postmodernism to modernism itself. The word latches onto modernism like a virus, infecting, tainting, mutating, and consuming it.

Jameson is careful not to brand this process of infection as negative. In the space of postmodernity all processes are created equal. However, his historical approach, even without moralizing, must ultimately confront the question of what kind of space “the space of postmodernity” is, and whether or not it will be a space in which we all can reasonably continue living. The realization that it exists at all is, for many, as frightening as it is seductive, and Kubrick’s film shows this. Hyperspace is a space that is terrifying and wonderful and created for all, a place in which we are able to witness the direct event of representation, which leaves us more afraid and more seduced by it as a result. As Jameson writes,

what has been called the postmodernist “sublime” is the only moment in which [truth] has become most explicit, has moved consciousness as a coherent new type of space in its own right.

This space, a collection of all spaces, gains power from its ruthlessly democratic collecting: in the new space, the typically marginalized “Negro cook” and a “willful boy” will succeed in the end. Their success stems directly from their evolved ability to “shine” through space and without time, and that ability is, in turn, contingent on their marginalized position.

In the end, Jameson writes, it is those that are most equipped to include what postmodernism omits that will be the embodied subjects of its texts, and this is a new cast of characters, indeed. His many trends – each “aspects” of behavior in the architecture of postmodernism – must, in the end, be viewed globally as well as locally. Both pose problems: there are, as he points out, “no true maps” for global spaces; one’s local space is one’s own, making its mapping impossible for anyone else. Yet, “cognitive mapping” is Jameson’s message in the end, for while the map includes in its form the incompleteness of postmodernism, it seems that in the rapidly expanding mazespace of the contemporary world, this incompleteness is quickly becoming an inevitability. If incompleteness must be an operating principle, then what separates a good map from a bad one is its usefulness on a local level and its specificity on a global level. For example, Danny’s mental map of the Overlook has local and global points of interest: “Redrum” is a communicade that is decidedly local – it is a warning from Danny to himself by way of a Through the Looking-Glass reversal. Meanwhile, Room 237 is global information – Holleran and Danny “shine” it to one another – and its specificity is underscored by Danny’s explicit enumeration of it to Holleran, asking, as he does, “What’s in Room 2-3-7?” This is precisely “cognitive mapping” as Jameson defines it:

to enable a situational representation on the part of the individual subject to that vaster and properly unrepresentable totality which is the ensemble of society’s structures as a whole.

It’s movies and TV and the Internet. Kubrick properly rewrote the end of The Shining properly to reflect this new aesthetic. With the father overwhelmed and immobilized, a mother and son navigate their way to safety down a road long since erased by snow.

-

In King’s text the hedge maze was actually a topiary garden in which the animals come alive and begin attacking the Overlook while the Torrances cower inside. ↩

-

This generic self-awareness is at its hilt during Jack’s conversation with Mr. Ullman, in which he admits that Wendy is “a confirmed ghost story and horror film addict.” ↩

-

Not surprisingly, characteristics surrounding The Shining come up during these sections. Jameson discusses Kubrick briefly in regard to depthlessness via the smooth black monolith of 2001. “It confronts its viewers like an enigmatic destiny,” he writes, “a call to evolutionary mutation.” He also discusses Jack Nicholson briefly in regard to historicity, claiming that stars like Nicholson, with their “well-known off-screen personalities,” imbue a film with a sense of their own personal history that is grounding and anti-postmodern. He suggests that actors such as William Hurt, who have an “utter absence of ‘personality’ in the older sense” help to maintain the “death of the subject,” which the postmodern requires. It is interesting, in light of this observation, to consider that Kubrick’s choice of Nicholson for the role may have extended beyond the star’s box-office draw, as Stephen King suggests in Collings’ book (King suggested Martin Sheen for the part). Casting a more “traditional” star (in Jameson’s sense) in the role allows one to observe the effect of the postmodern on the traditional, an effect that you can’t observe otherwise unless you’re familiar both with King’s story and with how Kubrick’s film diverges from it. The effect disturbed audiences profoundly, for while they had seen Nicholson play madness before in Milos Foreman’s critically-acclaimed and widely-seen One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975), his performance in Kubrick’s film was eerily different, causing both critical and popular unease about Nicholson’s performance immediately after its release. ↩

-

Most suggestive in this regard are Milena Canonero’s costumes, which often quote from Disney movies and children’s books. On “Tuesday,” Wendy wears a costume identical to Pippi Longstocking’s, and whenever Danny is confronted by Grady’s murdered daughters, they wear the light blue smocks of Disney’s Alice in Wonderland, their not-quite-twinness underscoring Kubrick’s technique of “twinning” (but not quite perfectly) the past into the present. ↩

-

One of Jameson’s references is worth including here. He cites Sartre, who describes Flaubert’s sentence structure as follows: “It closes in on the object, seizes it, immobilizes it, and breaks its back, wraps itself around it, changes it to stone and petrifies the object along with itself. […] It falls into the void, eternally, and drags its prey down into that infinite fall. Any reality, once described, is struck off the inventory.” It is interesting that Sartre describes such a violence that bleeds into petrification – such is the trajectory of The Shining, as Jack is literally frozen into stone by the end, the Overlook having “wrapped itself around” his own sense of self completely. Curiously, the image that follows that of Jack frozen inside the hedge maze is a long, slow zoom into a photograph of the Overlook’s Gold Room on the 4th of July, 1921 into which Jack has obviously been inserted. Jameson anticipates this juxtaposition of images, concluding from Sartre’s comments that “I am tempted to see this reading as a kind of optical illusion (or photographic enlargement).” ↩

-

While references to childrens’ stories abound in the script (“Come out, Come out, wherever you are” as Jack searches for his family in the hotel; “Little pig, Little pig, let me in” as he chops his way into the bathroom), Wendy’s remarks in the kitchen – that she’ll have to “leave a trail of breadcrumbs just to find [her] way out” – is particularly overt, as it comes shortly after she compares the space of the kitchen to a maze. Just as the hedge maze is a metaphor for the Overlook, her comment is a cleverly nested reference-within-a-reference-within-a-reference-within-a-reference: first to the kitchen, then to the maze, then to the house, then to Hansel and Gretel. These complex allusive moments are themselves a kind of syntactic maze. Such is the nature of language in Kubrick’s world – looped, leading nowhere, or maybe everywhere depending on how the path is mapped. In this labyrinthine way, Kubrick’s structure more recalls the stories of Jorge Luis Borges than Stephen King. ↩

-

Ullman’s conversation with Jack – more warning than welcome – is also more history than logistics. In giving the Overlook its Genesis story, its hyperspatial position as a world unto itself is all the more iron-clad. ↩

-

The image of the hedge maze is good to revisit. With its 13 ft. walls, “it is an element in which you yourself are immersed, without any of that distance that formerly enabled the perception of perspective or volume.” That’s actually Jameson describing the Westin Bonaventure’s lobby. As he continues his discussion of the lobby, his observations get even more eerily spot-on. ↩

-

Compare this to HAL’s way of seeing in 2001. ↩

-

There is a sidelong reference to Le Corbusier’s Towards a New Architecture here, and it is the same text from which the idea that “the plan is the generator” originates. Le Corbusier’s late Modern notions of architecture that both inspired and inflamed the postmoderns. His “superblocks” are nothing if not exactly the kind of vast, hyperreal spaces Jameson describes. His notions of machinery, however, are rather antiquated, stemming from the French art movement L’Esprit Nouveau. ↩

-

During one shot, the shadow of the helicopter is seen briefly in the corner, Kubrick’s subtle way of describing the machine without actually representing it. ↩