Fair Trade

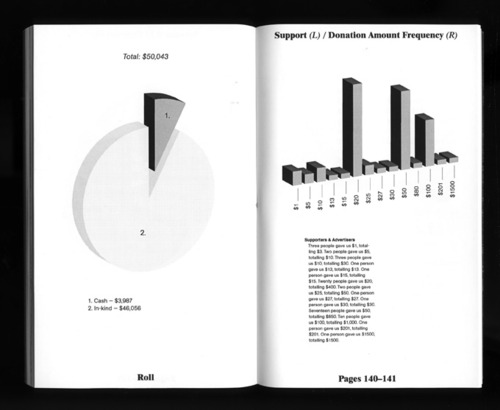

Above: A spread from The Book Trust Prospectus by IFS, Ltd.

This year, much of the talk about the New York Art Book Fair seems to be centered on the Fair itself. Fueling some of this talk, whether expressly stated or not, is a simple question: how, in the midst of one of the most historic economic recessions on record, as the media outlets decry the final hour of the book, was last year’s Fair the biggest yet? And why does it seem that this year’s Fair may be even bigger still?

Against the backdrop of the recession and the destabilization of the book there are three additional factors that have a bearing on the Fair’s ever-increasing reach: the graphic design postgraduate program that defines a thesis book as its culminating project; the design social scene that functions a bit more like a rock scene, celebrating the making and distribution of new work over the more professionalized goals of acquiring and servicing clients; and the temporary or “pop-up” store that transforms the sometimes solitary act of buying into a networked, participatory, and collective event.

At the start of The Program Era, his study of the influence of postgraduate creative writing programs on postwar American fiction, Prof. Mark McGurl asserts that “the rise of the creative writing program stands as the most important event in postwar American literary history.” The same may be true our postgraduate design programs today. During the recession, designers have enrolled in these programs in record numbers, turning to the academy as fewer jobs and clients are to be found. If we look to McGurl as an example, the creative results of this widespread enrollment may soon, to use his phrase, be “everywhere visible in the texts as a kind of watermark.” For graduates of these programs, early notice often takes the form of design blogs, which monitor degree shows and are read largely by other students, designers, and design enthusiasts. Returning to the rock analogy, publishing work on one of these blogs might be equated with the release of a new single by an emerging band; in fact newness is the mode, and a meaningful contribution (along with perhaps a modicum of notoriety) the ostensible objective. Names get known, the best work gets celebrated, spurs new work, and the cycle of influence turns once again.

These design networks make it possible to “know” or even “follow” the work of more designers than ever before. And once you feel you know someone, it’s natural to want to reach through the Internet to shake hands and trade goods. The Fair enables this impulse, encouraging the exchange of books, in order to frame, or even ritualize, this movement from the virtual to the real. While these transactions are often microcapitalist and cash-based — at times, the classic lemonade stand image comes to mind — this year’s Fair features two projects that are not. The Werkplaats Typografie’s project is based on bartering and invokes the circulating metaphor of a library. And IFS Ltd.’s project is based on speculation, asking friends and followers to financially support a book that is, in one sense, the story of its own fund-raising or publishing while containing the potentially new tale of where it will move and how far it will go. Both projects tweak the economic concept of “stock and flow” to creatively productive ends, taking a common inventory (books produced by either group) and diversifying it to accrue new value as the common stock changes hands and flows outward into the marketplace. In in both projects, the system of exchanges will leave participants feeling more “invested” in the books they’ve acquired and in the people from whom they’ve acquired them.

For bookstores, the Long Tail of infinite shelf space and the elimination of middlemen in the supply chain along with increased transparency in pricing has either forced book prices down (as it has at big box retailers like Target and Walmart) or evened them out (as it has at internet retailers like Amazon or specialist sites like AbeBooks or BookFinder). New modes of distributing the “book” itself, either electronically or with on-demand printing, further challenge not only booksellers but book manufacturers, wholesalers, and publishers right up the chain. For books where content is separable from physical form — the book-as-markup — one of these two methods of distribution will likely become the rule, leaving booksellers to reckon with the results.

But while there may be other ways of getting books if not from bookshops, there’s a distinct loss at a local level without them there. “The local bookstore creates all kinds of value for its community, whether it’s providing community bulletin boards, putting rocking chairs in the kids section, hosting book readings, or putting benches out in front of the store. Local writers, harried parents, couples on dates, all get value from a store’s existence as a inviting physical location, value separate from its existence as a transactional warehouse for books,” wrote Clay Shirky last year in a post titled “Local Bookstores, Social Hubs, and Mutualization.” At the conclusion of the piece, he proposes “trying to save local bookstores from otherwise predictably fatal competition by turning some customers into members, patrons, or donors” — though it’s not exactly what he had in mind, for three days the visitors, booksellers, participants, and networkers at the Fair are precisely that.

So what, then, of books and their makers? In the case of the book-as-markup mentioned earlier, its fabrication was once the purview of jobbing typesetters and fine printers. Now this kind of book is available for output across a wide range of devices, formats, and screens. And while e-readers like the Kindle seek to acclimate the readers of actual books to a new reality by retaining the book-like trappings of pages, bookmarks, and serif printing types, there’s nothing keeping the same device from outputting the same text as an unending tagged scroll in sans-serif backlit type for reading in bed, or as a scatterplot of most-cited quotations by readers on a particular continent for scholarly analysis. In this iteration of the book, the only labor required to produce it is the labor required to write it and distribute it. The labor of giving it one of its many potential forms is either front-loaded to the device manufacturer or offloaded to the readers themselves as a set of user preferences or stylesheets.

In the case of another sort of book, the book-as-artifact, its creation has long been the purview of artists, professional graphic designers, and art book publishers. While they may not always be wedded to the book form in the sense of a codex — many artists’ books and multiples actually do away with this most “book-like” of book qualities — books-as-artifacts are always wedded to objecthood itself and are lushly aware of their materiality, coming slipcased or belly-banded or oversized or hand-stamped or somehow otherwise ceremonial and laudatory. The reproductions certainly far surpass anything on a screen. The whole production is handsome and tasteful, something that’s likely displayed on a coffee table or carefully catalogued by a dealer.

There are many of these sorts of books, and many of them are wonderful too, and some of them can be found and browsed at the Fair, but not many of them will be bought there: they feel a bit remote from its aims. They are a bit expensive for one thing; books at the Fair are, for the most part, affordable. For another thing, these books-as-artifacts reiterate an existing power structure, particularly when it comes to the relationship of the art and design world; the Fair, though, seeks a different kind of order. Instead of relying on books to bolster established careers, books at the Fair more often showcase new talent, particularly when it comes to the making of the book itself. And it is not enough, in the eyes of many, to simply generate the files for output; now the book must be “made” through and through, editioned in a small number, output using inexpensive or cast-off printing technology and distributed one-by-one by the makers themselves, all of whom come together in one place for one weekend in a kind of superstore of mass localization. These are books that are meant to travel and be traded, to circulate and be charted, to grace the shelves of colleagues and to define another class of book that is just the kind of book that’s found at the Fair. The book produced by IFS, Ltd. is fueled in part by the speculative efforts of a community within a marketplace that mirrors this action. It is vanity publishing born out of communal necessity, and it is, every year, my favorite time, my favorite place to see friends, to swap copies, to drop cash, to grab coffees, and to take part in that common and much-loved thing I hope will always remain as vital as it feels now, in spite of all the gloom and doom. That is, the making and sharing of books.

This piece was commissioned by IFS, Ltd. for their project The Book Trust Prospectus at the 2010 New York Art Book Fair.